We All Came from Somewhere Else

/A view of Charles-Town, the capital of South Carolina / painted by Thos. Leitch ; engraved by Saml. Smith. Library of Congress

Long before Flat Rock became a retreat for Lowcountry planters and a magnet for artists and retirees, the people who shaped this mountain village arrived from somewhere else. Some came willingly, chasing opportunity or health. Others were brought in chains, their passage a tragedy that would reverberate for generations. Cherokee and other early peoples who lived here first were displaced by the tide of newcomers.

This is the truth of Flat Rock’s history. It is a place created by immigrants who displaced local Native Americans. It is a reminder that the American story - whether chosen or forced - has always been one of aggregating knowledge, skills, and traditions from a diverse array of cultures.

Judge Mitchell King

Crail, Scotland (1)

Born on June 8, 1783, in the ancient fishing village of Crail, on the rocky coast of Fifeshire, Scotland, Mitchell King grew up with the tang of salt spray in the air and the cry of seabirds over the North Sea. Restless and ambitious, he set off in 1804 at age 21 for Malta, dreaming of a merchant’s life, only to sail straight into legend.

Argyle CA 1930s

Spanish pirates seized his ship and hauled the young Scot to Málaga as a prisoner. For months, he endured the uncertainty of captivity in a foreign land. In September 1805, he escaped and secured passage to Charleston, South Carolina, stepping onto a bustling seaport that would become his lifelong home.

Charleston soon rewarded King’s intellect. He opened a private school and, within six months, earned a teaching post at The College of Charleston. In 1810, he was admitted to the South Carolina bar. Over the decades, he rose to wealth and influence and became the father of eighteen children.

A business trip in 1828 to investigate the idea of linking a railroad from Charleston with western North Carolina brought King to the cool mountain air of Flat Rock. It was there, in the crisp climate, that King’s wife found relief from the asthma that tormented her life. As a result of his wife’s dramatic improvement, King began buying land - sometimes for as little as twenty-five cents an acre - until he held nearly 7,900 acres.

In 1830, King purchased the 1,390-acre “Saw Mill Tract” from Colonel John Davis, land originally granted after the Revolution to Abraham Kuykendall and D. Miller. The property included a house, sawmill, furniture factory, and other buildings. The original house, built around 1815, forms the heart of Argyle today, making it the oldest dwelling in Flat Rock and one of the settlement’s first two homes. King named his summer retreat Argyle after his wife’s ancestral county in Scotland.

In 1838, King donated fifty acres to establish Hendersonville as the county seat, cementing his role as a founding father of Flat Rock and what would become Henderson County.

Christopher Gustavus Memminger

Württemberg, Germany

Christopher Gustavus Memminger’s life began like a chapter from a Dickens novel, full of tragedy, reversal, and improbable triumph. He was born on January 9, 1803, in Vaihingen, a quiet village in the German state of Württemberg (today part of Stuttgart)

C.G. memminger

His father, an army officer, was killed only weeks after Christopher’s birth, fighting for the Kingdom of Württemberg against Napoleon. As a result, his widowed mother, Eberhardina Köhler Memminger, carried her infant son across the Atlantic to Charleston, South Carolina, hoping to join family and start anew.

Sadly, Charleston, with its elegant homes and humid harbor, offered Memminger’s mother no reprieve and she died of yellow fever when Christopher was just four. The orphaned boy was placed in Charleston’s Orphan House. There, his quick mind and quiet determination began to shine.

At eleven, he caught the attention of Thomas Bennett, a prominent lawyer and future governor of South Carolina. Bennett brought Christopher into his own household, gave him the education of a gentleman, and in doing so altered the boy’s fate.

By age twelve, Memminger was studying at South Carolina College. By sixteen, he graduated second in his class. He passed the bar in 1825, a young attorney with a crisp mind for numbers and argument. Charleston society took notice. He married Mary Withers Wilkinson and built a career as both lawyer and legislator, serving for twenty years as chairman of South Carolina’s powerful Finance Committee.

Through the 1830s, he opposed the state’s early attempts at nullifying federal law, but politics hardened in the decades to come. After Abraham Lincoln’s election, Memminger - once the cautious moderate - was called upon to draft the South Carolina Declaration of Secession, the ringing legal brief that justified the state’s break from the Union

When the Confederacy formed in 1861, Jefferson Davis appointed him Secretary of the Treasury, entrusting him with the desperate task of financing a war without an established currency. By 1864, amid runaway inflation and political criticism, he resigned his post.

Through it all, his refuge lay in the cool highlands of Flat Rock. In the 1830s he had built a summer estate he called Rock Hill at the foot of Glassy Mountain. During the Civil War, his property became a fortress of sorts. The home’s windows were barricaded with sandbags and portholes cut into doors so defenders could fire at roaming bushwhackers. Friends and relatives sought shelter with the Memmingers in those uncertain times

After the war, he received a presidential pardon and returned to Charleston to rebuild his life. He re-entered the legislature and threw himself into a cause that had long stirred his passion: public education.

Memminger’s story ends not in the turmoil of war but in the quiet of the mountains he loved. He died in 1888 and, in accordance with his wishes, was buried beside his wife Mary in the churchyard of St. John in the Wilderness Episcopal Church in Flat Rock.

Charles and Susan Baring

England/Wales

When Charles Baring, a younger member of London’s famed Baring Brothers banking family, stepped off the ship in Charleston in the 1820s, his errand was simple. He was tasked with arranging a marriage between his cousin, Lord Ashburton, and the wealthy widow Susan Cole Heyward.

Susan Baring

Cupid (or financial incentive?), however, re-routed the deal. Welsh-born, formidable, and already widowed multiple times, Susan soon captivated Charles, and Lord Ashburton was quickly supplanted by his cousin. With Susan’s Lowcountry fortune and Charles’s European polish, the pair formed a transatlantic alliance tailor-made for reinvention in the Carolina mountains.

As was true for so many others, Charleston’s sweltering summers and malaria imperiled Susan’s health and Charles went scouting for altitude and clean air. He found it on a granite shelf in the Blue Ridge known as Flat Rock.

In 1827, the Barings raised Mountain Lodge, a Greek Revival house set up like an English country estate. Their purchases grew to about 3,000 acres, and, in tandem with Judge Mitchell King, their accumulations and resales helped seed a lattice of summer estates that would become “Little Charleston in the Mountains.” The Baring’s Mountain Lodge was among the settlement’s earliest grand homes and a tone-setter for the colony’s style of living.

Perhaps most consequentially for the nascent settlement, the Barings also brought their Anglican faith. Their first private chapel, a small wooden structure on the estate, burned in a woods fire. In 1833, they replaced it with a brick church and, three years later, deeded it to the Episcopal Diocese, reserving pews for the family and burial ground beneath.

Thus, was born St. John in the Wilderness, the oldest Episcopal parish in Western North Carolina. The name of the church is perhaps a nod to Flat Rock’s old designation as part of “the wilderness,” or perhaps a sentimental echo of an ancient St. John in the Wilderness near the Baring family’s ancestral home in Devon.

Susan’s death in 1846 changed everything. Much of her wealth reverted to the Heyward heirs, and Charles sold Mountain Lodge to Edward Trenholm. Charles remarried and built another summer place in Flat Rock called Solitude near today’s Highland Lake.

What the Barings left behind was more than architecture. Their English parkland aesthetic, their parish church, and their enthusiasm for the climate drew friends from Charleston up the turnpike until the place felt like a transplanted Lowcountry. The social grammar of Flat Rock, its blend of refinement, retreat, and community, owes much to this English-Welsh partnership that went looking for health and, almost by accident, founded a way of life.

Count Joseph Marie Gabriel St. Xavier de Choiseul

France

Count Joseph Marie Gabriel St. Xavier de Choiseul carried with him the quiet grandeur of the old French nobility. A cousin to King Louis-Philippe, he belonged to a family whose name was bound to centuries of diplomacy and intrigue in Europe.

Gardens at Chanteloupe

In the unsettled years after the French Revolution, the count crossed the Atlantic and accepted an appointment as French consul in Charleston, a city that offered both the elegance of a European port and the opportunities of a new republic

By the summer of 1836, seeking relief from Charleston’s humid air, the count followed his friends Charles and Susan Baring to their highland retreat in Flat Rock. Perhaps the mountain climate, cool and scented with pine, reminded him of the wooded estates of home. That same season he purchased land from the Barings and built Saluda Cottages, a modest main house flanked by two smaller cottages. It was a refined little enclave whose very name, drawn from the nearby Saluda River, suggested both Europe and Carolina frontier.

The count’s ambitions quickly outgrew his first house. On a nearby 300-acre tract known as the William Capps tract, he began an even grander vision - a stone residence that neighbors soon called “The Castle.” The approach led through a deer park, then along rows of white pines to a broad west-facing terrace. Contemporary visitors spoke of the grounds descending in meadow and willow-bordered stream, and of a house designed in the manner of a French château, an unmistakably foreign presence in the rugged Blue Ridge. Today, the house still stands and is known as Chanteloupe.

While the count often returned to Charleston and occasionally to Savannah for his diplomatic duties, Sarah, Countess de Choiseul, and their daughters held the mountain seat year-round. By 1840, four members of the family were on the rolls of St. John in the Wilderness church.

The de Choiseuls’ eldest son, Charles, embraced his adopted land. In 1840 he took the oath of allegiance, and the following year was elected county surveyor, his signature appearing on some of the earliest surviving maps of Henderson County

But the family’s story turned bittersweet. Sarah, the Countess, died in 1859, and the Castle was sold in 1861. Charles left for New Orleans, where on June 4, 1861, he entered Confederate service as Lieutenant Colonel of the 7th Louisiana Infantry. He was mortally wounded at Port Republic on June 9, 1862, and died ten days later. His body was brought back to Flat Rock and buried beside his mother at St. John in the Wilderness.

Despondent over the death of his wife and his son, and fearing a Union blockade of the port of Charleston, the Count de Choiseul left Charleston late in 1862 and lived out his days in France. He died in Cherbourg, France in 1872.

A granite marker with a bronze plaque, placed by the United Daughters of the Confederacy, still stands over Charles’s grave, and a French flag gifted in his honor hangs in the church’s tower room.

Abraham Kuykendall

Dutch Roots in the New World

Long before Charleston planters began building their summer estates in the Blue Ridge, Abraham Kuykendall had already carved a homestead from the wilderness. Born in 1719 in New York’s Hudson Valley, he was the grandson of Dutch immigrants who had settled there when the colony was still known as New Netherland, a place of broad rivers, rich farmland, and stubbornly independent traders. From those early Dutch settlers Kuykendall inherited a practical mind and an eye for opportunity.

Memorial to Abraham Kuykendall at Mud Creek Baptist Church

A man of restless energy, he moved south in the mid-18th century, first through Virginia and then into the Carolina backcountry when it was still a patchwork of Cherokee hunting grounds and rough-hewn frontier settlements. He arrived with the skills of a pioneer and the instincts of a merchant. By the 1770s, Kuykendall had become a recognized figure in the region, serving as a militia captain in the Revolutionary War, defending frontier homesteads when the struggle for independence threatened his mountain home.

By the late 18th century, Kuykendall had assembled over a thousand acres in the broad, rolling lands that would later be called Flat Rock, decades before the Charlestonians discovered the mountain refuge. His holdings straddled the Old State Road, the rough wagon route connecting South Carolina to the western mountains, and he turned that location into a small empire of enterprise with a tavern where travelers could rest and water their horses, a grist mill to serve scattered farms, and a distillery whose barrels of corn whiskey were said to be among the best in the region.

Kuykendall was also a man of faith and community. He donated land for Mud Creek Baptist Church, which became one of the area’s earliest centers of worship and fellowship

Interestingly, Kuykendall’s legend lives as much in folklore as in deeds.

As the story goes, sensing death in 1812, the old Dutchman buried a pot of gold and silver coins somewhere on his property. On his deathbed he tried to tell his kin the hiding place, but his speech failed, and the words came out garbled. The treasure has never been found.

For more than two centuries, locals have whispered of the “bugger branch,” a creek where, some say, the ghost of Abraham Kuykendall still wanders with a lantern, eternally searching for his lost hoard.

Whether fact or fable, the tale captures the spirit of a man who brought the industrious vigor of the early Dutch settlers into the Carolina mountains—a pioneer whose enterprise helped lay the groundwork for the community long before Flat Rock became “Little Charleston in the Mountains.”

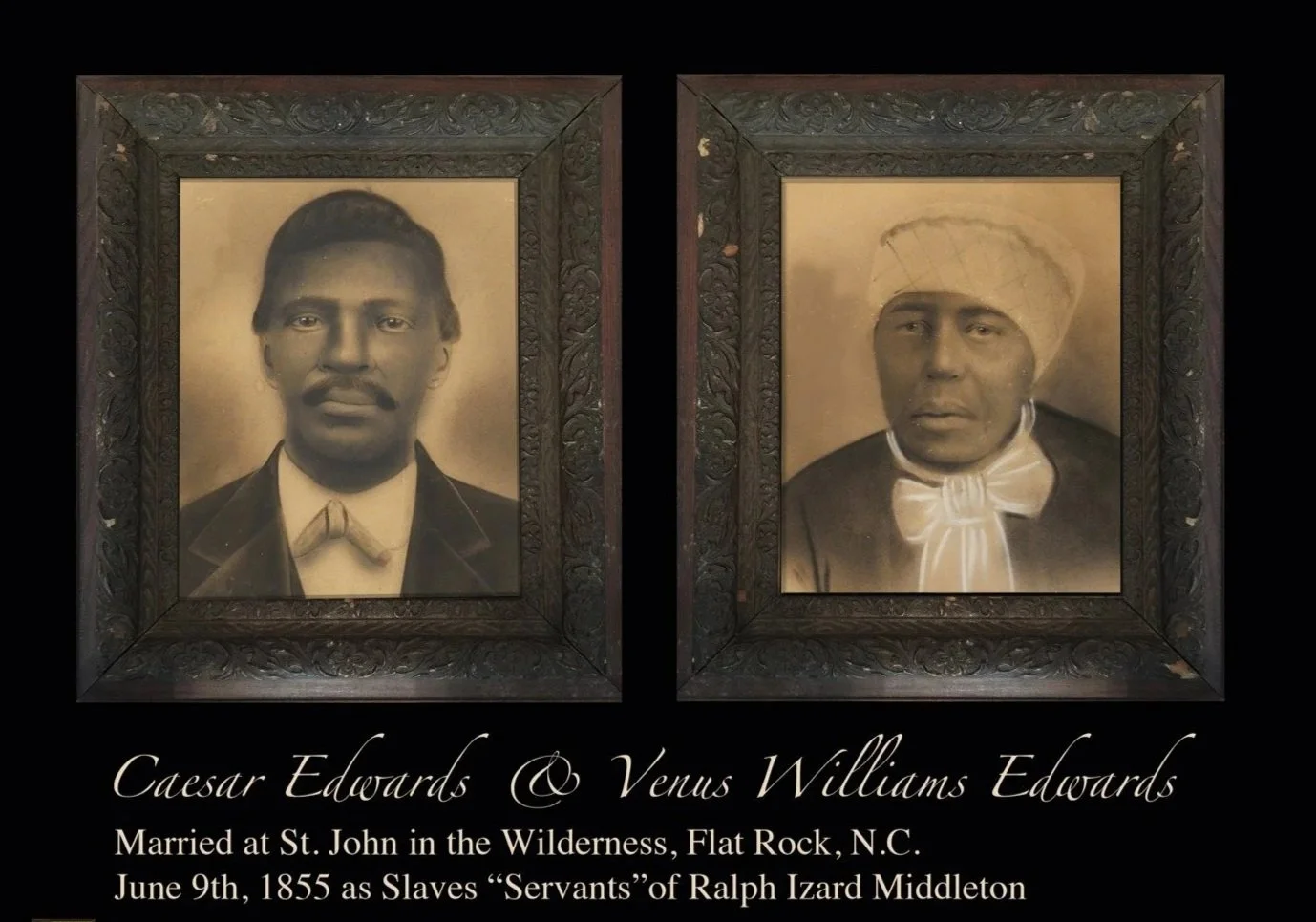

Caesar Edwards and Venus Williams Edwards

Exact Origin Unrecorded

Flat Rock’s story cannot be told without the people whose arrival was not of their own choosing. Beginning in the late 1600s, the harbor of Charleston became one of the busiest slave ports in North America. Slave ships from Senegambia, Sierra Leone, the Windward and Gold Coasts unloaded thousands of West Africans who carried with them not only their own languages and beliefs, but also hard-won agricultural knowledge—especially the sophisticated techniques of wet-rice cultivation that Lowcountry planters eagerly exploited.

Caesar and Venus Williams Edwards

These men, women, and children were sold at the wharves and driven to plantations that stretched from the tidal rice fields of the coast to the upcountry mountain valleys. By the early nineteenth century their forced labor underpinned the very prosperity that allowed wealthy Charleston families to build their summer retreats in the cool heights of Flat Rock.

Enslaved people felled the trees, quarried the stone, and raised the homes and gardens that became the showplaces of the colony. Their sweat is in the mortar of Mountain Lodge and Rock Hill, Their quiet endurance shaped the landscape as surely as the mountain streams.

Among those whose names we know, Caesar Edwards and Venus Williams stand out as a testament to resilience. Enslaved by members of the Middleton family, they found in one another a measure of strength and hope. On a June day in 1855, while still legally property, they were married at St. John in the Wilderness, the Episcopal church founded by the Barings. The ceremony. sanctioned by neither freedom nor equality, was nonetheless a profound act of self-definition.

When emancipation came a decade later, Caesar and Venus stayed in the place where they had been enslaved and transformed it into home. In the 1880s they scraped together enough savings to purchase their own land, a milestone of independence that echoed across generations. They became charter members and leaders in the founding of Mud Creek Missionary Baptist Church in East Flat Rock, a congregation that offered spiritual refuge and a center for the Black community’s social life during Reconstruction and beyond.

Their perseverance—and that of countless others whose names were never recorded—laid the foundation for a vibrant African American presence in Henderson County. The descendants of the enslaved continued to build schools, churches, and businesses, shaping the region’s culture long after the summer visitors from Charleston had gone.

Today, the quiet churchyards and family plots of East Flat Rock are not only places of remembrance but living proof of a people who turned bondage into belonging, ensuring that the history of Flat Rock is inseparable from the courage and creativity of those who came here in chains.

The First Caretakers

The Cherokee and Earlier Peoples of the Blue Ridge

This account of early Flat Rock would be remiss without recognizing the reverence for, and stewardship of, this place by the earliest inhabitants of the region.

Long before European wagons rolled up the Saluda Path, the high ridges and hidden coves of western North Carolina were the homelands of the Cherokee and their ancestors. For countless generations, they moved with the rhythm of the seasons, building towns along the broad river valleys and traveling well-worn trails over the mountains. The land was more than a setting for life; it was a living presence. Aniyvwiya, the “Real People,” saw themselves as kin to the forests, waters, and creatures that surrounded them.

The mountains themselves were sacred, their peaks seen as ancient beings whose shoulders caught the first light of day. Cold springs and tumbling creeks were regarded as places of renewal and healing, where the water’s spirit could cleanse both body and soul.

This reverence shaped a careful stewardship. Fields were planted in the rich bottomlands and then allowed to rest; fire was used with precision to clear meadows and keep forests healthy. The vitality and beauty of the Blue Ridge that modern visitors marvel at today is, in no small part, the legacy of these centuries of mindful care.

In the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, the balance broke. Waves of European settlers pressed into the southern Appalachians, eager for land and timber. Treaties were signed and broken. By the 1830s, federal policy known as the Indian Removal Act, forced most of the Cherokee from their mountains onto the brutal march west that became known as the Trail of Tears.

A small number eluded removal, hiding deep in the coves and later forming what is now the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians. Their survival kept a living thread of Cherokee culture in these hills, but the vast homelands were forever altered.

The forests, rivers, and wildlife of the Blue Ridge still carry their imprint. To walk the trails of Flat Rock and the greater Carolina mountains is to follow paths first shaped by Indigenous feet, to see through trees that were once prayed over, to hear waters that were once sung to. The Cherokee and their forebears were, and remain, the first caretakers of this land, and the enduring beauty of western North Carolina owes much to their ancient and abiding reverence for the natural world.

--

Flat Rock’s early history reads like a world atlas: Scotland, Germany, England, Wales, France, the Netherlands, West Africa – with the deep roots of the Cherokee and earlier peoples. Their legacies of buildings, churches, civic institutions, and family lines, are the bones of the community we know today.

To travel our mountain pathways and enjoy the beauty of this place we call home is to be reminded that what we celebrate as uniquely Flat Rock is, in truth, the creation of people who came from afar. Whether by choice or by chains, they brought with them skills, traditions, and dreams.

Ultimately, their stories are a vivid reminder - we all came from somewhere else.

(1)Sources

King:

Historic Flat Rock, Inc.

Argyle

Village of Flat Rock

Memminger:

Ncpedia

Citizens-Times

Baring:

Village of Flat Rock

St. John in the Wilderness

HendersonvilleBest.com

de Choiseul:

Flat Rock, Sadie Smathers Patton

Historic Flat Rock, Inc

HendersonvilleBest.com

Kuykendall:

HendersonHeritage.com

Edwards:

Blue Ridge Now; Ruscin

“African American History in Henderson County Part Two”, Missy Izard

Hendersonville Times-News