A Seat on the Bus

/In the 1950s, Montgomery, Alabama’s city ordinance required Black riders to sit in the back half of the bus and give up their seats if the front section filled. The Montgomery Bus Boycott began on December 5, 1955, just days after Rosa Parks was arrested for refusing to yield her seat to a White man, and lasted for 381 days.

Flat Rock resident Jean Ross and her family lived in Montgomery in the months leading up to one of the most seminal moments in American history.

A Seat on the Bus

by Jean Ross

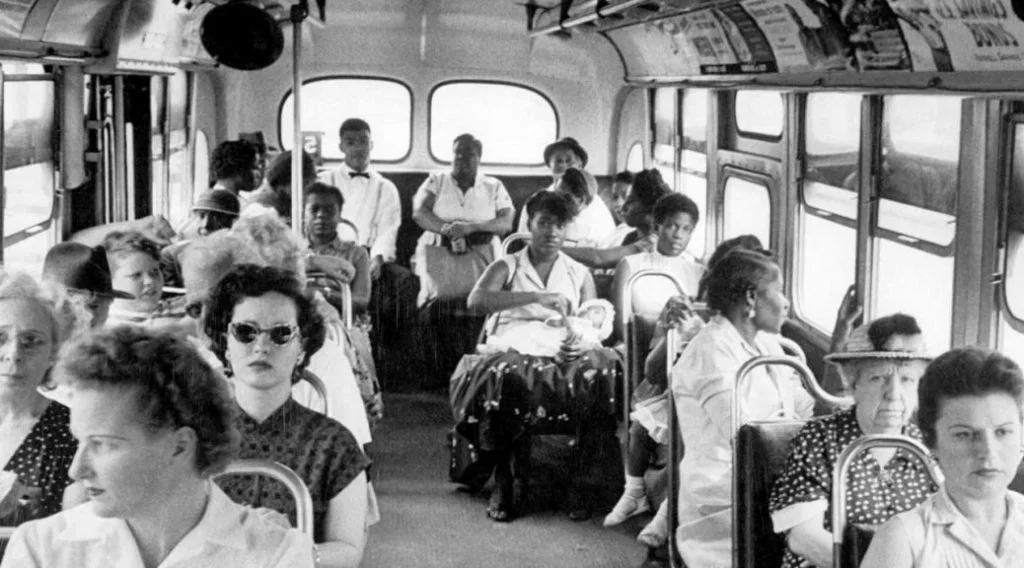

a segregated bus in montgomery, Alabama during the 1950s. Stan WAyman

Hattie was small, wiry, and amazingly strong. Two and sometimes three days a week, she came to our house for a few hours; both my parents were at work. She washed, ironed, cleaned a bit, and on our lucky days made the best thin, flaky biscuits I’ve ever eaten in my life.

They’d be rolled out and ready to pop in the oven for dinner, with enough to spare for the next night’s meal. But before she put these in the refrigerator for baking later, she’d plop the leftover cuttings onto a baking sheet and cook those for my brother and me. Slightly brown, best smell in the world, eaten with a bit of butter on the top that melted into a pool before we could get them into our mouths.

Hattie and her husband had a number of children, some of them adopted; I don’t remember exactly how many there were. They’d all been to college or were going. This was a great source of pride to the couple. They had a car, but Hattie’s husband took this to work—he had a job with one of the railroads—and she took the bus to and from our place on the days she came.

We also relied on the city buses for getting anywhere more than a mile or so from home; we had no car. And this is part of why the bus incident happened. I had come home from school but wanted to go downtown. Hattie was through for the day, so we were heading in the same direction. Off we went, chatting away as we walked the three blocks or so to the bus stop. One of the things I liked about her was that she routinely talked to me as if I weren’t a stupid teenager, though she could and did scold me when I was.

The bus came. We got on. Where to sit? She was supposed to sit at the back. I was supposed to sit elsewhere. It seemed not quite right that we should part company when we could keep talking all the way to town. So, not really saying anything about it, we chose a seat to share in what seemed like the front of the back.

Jean Ross in High School

There were few other people on the bus at this hour. The white people who were on the bus studiously ignored us, and we really didn’t think about them. We were aware that the bus driver glowered at us in the interior rear-view mirror, but we didn’t fret about it. We kept talking until we came to the stop we were both headed for and got off together, then parted to go our separate ways.

A few days later, my mother reported that our neighbor directly across the street had accosted her about this. I don’t know how he knew; I didn’t remember seeing him on the bus. This wasn’t the done thing, and he wanted Mother to know I had broken an important rule. Mother, as she told the story to me, said to him, “So what?”

This didn’t satisfy my neighbor; he confronted me directly about it. Having been alerted, I responded with some version of Mother’s earlier “So what” and didn’t answer back when he said I shouldn’t have done it. We weren’t popular with this family after the incident. Their son was no longer allowed to play with my brother.

The bus incident and its fallout happened in Montgomery, Alabama, a year or two before the bus boycott.

As I reread this in 2025, I think about how things have changed, not enough, but still for the better. I think about how much more change is needed and how to protect the good that has been achieved. I am afraid that young people may not learn or understand the bitter, brave history of how we have come this far.

On another plane, I am grateful for my parents, who by word and deed always questioned the status quo and taught my brother and me to do the same.

—

Postscript:

RRosa Parks being fingerprinted by Deputy Sheriff D.H. Lackey after being arrested on February 22, 1956, during the Montgomery bus boycott. Public domain.

Rosa Parks’ arrest sparked an unprecedented response: approximately 40,000 Black bus riders - the majority of the city’s ridership - stayed off the buses on the first day of the boycott. That same afternoon, local leaders formed the Montgomery Improvement Association, electing 26-year-old Martin Luther King Jr. as president

Though initially focused on courtesy, fair seating, and hiring Black drivers, the boycott eventually led to a federal lawsuit challenging segregation. On June 5, 1956, a district court ruled bus segregation unconstitutional; the U.S. Supreme Court upheld that decision later that year. On December 21, 1956, Montgomery’s buses were integrated.

—

About the Author:

Jean is a retired technical writer and consultant, as well as a social worker, who spent much of her career at a Columbia, SC, book publisher and the University of South Carolina. She also served as Director of Resource and Curriculum Development for the South Carolina Foster Parent Association and worked for the Domestic Abuse Center in Columbia as a group leader and supervisor.

A graduate of Spalding University, where she studied English and Communications, and the University of South Carolina, where she earned her Masters in Social Work, Jean is known for both clarity of expression and a deep commitment to social issues.

Raised in Alabama during the 1950s, she experienced firsthand the inequities of the Jim Crow South and the rise of the Civil Rights Movement--an era that continues to shape her perspective. Today, Jean makes her home in Flat Rock, NC, where she enjoys retirement and a complicated relationship with apostrophes.

A Follow-Up Interview with the Author

FRT: What are your memories of Hattie? Do you have a photo of her?

Jean: No, I never had a photo of Hattie. I wish I had. I remember her so fondly.

She was always kind. Even though I was just a teenager, she always talked to me like I was an adult. One of the things I loved about her was that she was no-nonsense. We could have a serious conversation, but if I was being a jerk, she would tell me.

She was an interesting person, and she was all business. She and her husband had a number of children, some that they gave birth to and some adopted. And college was the goal for all of those kids.

When my great-grandfather was dying in Birmingham, Hattie traveled from Montgomery and suddenly appeared at the door and said, “What can I do? I'm here to help.”

FRT: You were a teenager at the time of this story. Did you understand the magnitude of what was happening around you?

Jean: I was very much aware of it. My parents were opposed to segregation, and my father and I had discussed it. What he said at the time was, “It's not right, but I don't think there's anything we can do about it.” That changed later when my parents retired and moved back to Birmingham.

FRT: As you sat on the bus with Hattie, did you understand the possible consequences of that simple act?

Jean: Yes, we were both well aware of the risk. My parents found it frightening during that time when they were working in Washington, DC, but sometimes needed to go back to Alabama to take care of my grandmother. They had Maryland tags on their car. In Alabama, Maryland was considered North.

FRT: Did your parents instill in you a sense of right and wrong as a child?

Jean: They very much did. We talked about things, and mainly my brother and I just watched them. They rarely accepted the status quo of anything. They questioned everything and made their own decisions about what they felt, what they believed, and how they behaved.

FRT: Were you living in Montgomery when Rosa Parks was arrested and the boycott began in earnest?

Jean: No. My family moved to the Philippines in June 1955 for my father’s work. But we followed the news of the boycott as much as we could.

FRT: Have you been back to Montgomery?

Jean: A few times. Some years ago, we made a trip to southern Alabama, where my parents had retired for the second time, on Mobile Bay. We stopped in Montgomery for a night on the way and stayed downtown. There was a big outdoor plaza with a mix of people eating, drinking, and dancing—just having a good time. It was about half Black and half White. I said, “It’s really encouraging, after growing up in Montgomery, to see this. This is progress."