House on the Rock

/“Everyone who has had the privilege of working and spending time on The Rock has a story to tell of the day or evening they arrived at the Playhouse… I distinctly remember the sense of overwhelming familiarity with the dwelling that stood in front of me and yet I knew I had never stepped foot on the property.”

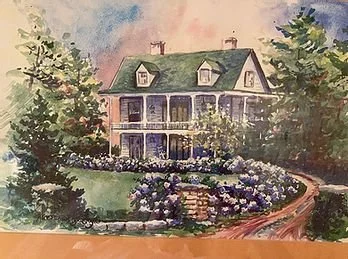

The Lowndes House on the Campus of Flat Rock Playhouse

There is something about the Lowndes House.

Even for those who have never crossed its threshold, it carries a curious sense of recognition. Sitting at the center of the village and perched elegantly atop its granite outcrop, it does not demand attention. It simply stands as a silent sentinel beside Greenville Highway, as a steady stream of traffic flows by and the seasons quietly shift.

Within its walls, however, reside stories at the very heart of Flat Rock’s history and cultural legacy.

For more than a century, the Lowndes House has stood at the intersection of two defining chapters of the village. First, the story of the Lowndes family, who helped shape Flat Rock into a Low Country summer refuge. And nearly one hundred years later, a second story of a young immigrant from Liverpool - Robert William Smith, whom we now know as Robroy Farquhar - whose theatrical vision transformed the Rock into the cultural heart of the region.

Taken together, these histories make the Lowndes House more than an interesting structure.. It is the place where those two stories meet.

Dolce Far Niente

The story of the Lowndes House reaches back long before theatre tents were raised, and stage lights glowed against summer dusk. It begins in the early 1800s with the Lowndes family of Charleston.

Thomas Lowndes, the son of Revolutionary-era South Carolina Governor Rawlins Lowndes, was a rice planter, a prominent figure in Charleston society, and a U.S. Congressman from 1801 to 1805. In the 1830s, drawn by the cool mountain air, he built one of the earliest substantial homes in Flat Rock and named it Dolce Far Niente - “Sweet Nothing to Do.”

The name captured the purpose of the house. Low Country families journeyed to western North Carolina to escape coastal heat and disease, and relax in the cool mountain summer air.

For more than a century, Dolce Far Niente stood across Greenville Highway from St. John in the Wilderness, until it was demolished in 1960. Today, a few tilting granite columns and clusters of old hydrangeas remain as quiet reminders of a vanished estate.

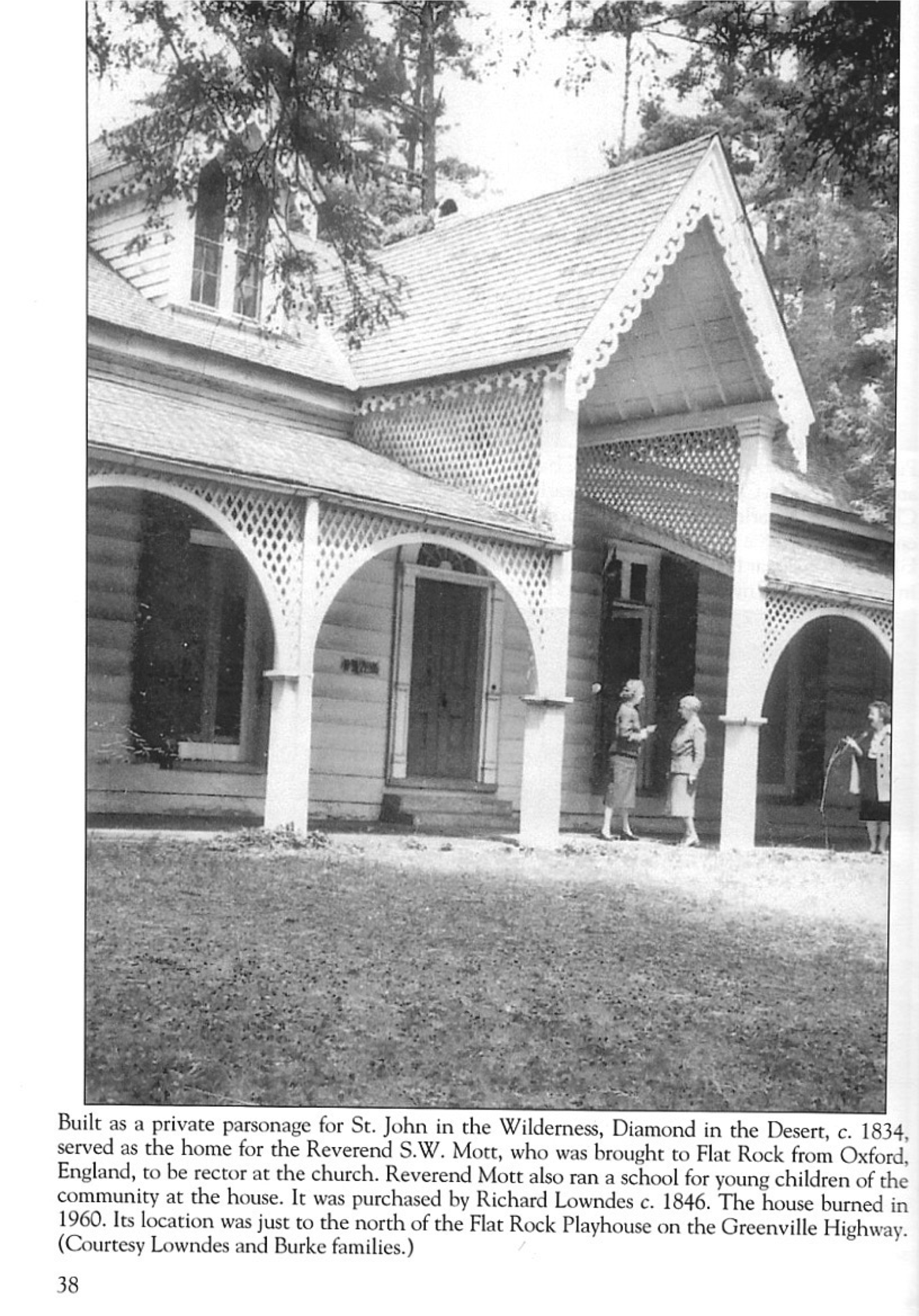

In 1846–47, Thomas’s son, Lieutenant Richard Henry Lowndes, purchased the former St. John’s rectory and renamed it Diamond in the Desert. It was located on the western edge of Greenville Highway – the Buncombe Turnpike at the time - between the current Playhouse campus and Boyd Drive. The house became both a family residence and a steadying presence through the upheaval of the Civil War. As Flat Rock slowly took shape as a summer colony, the Lowndes family stood at its center.

Sadly, the house was struck by lightning in 1960 and burned to the ground. Today, the site is a heavily wooded lot that holds only memories of its former glory.

Then, in 1884, Richard’s son, Richard I’on Lowndes, built a two-story home directly atop the massive granite outcrop along the southern edge of his father’s land. Six acres stretched around it, but it was the stone beneath - the great flat rock that gave the village its name - that defined the property.

The newest Lowndes residence was simply called “The Rock.” That house, rising from granite rather than resting beside it, is what we know today as the Lowndes House, grandly situated on the campus of the Flat Rock Playhouse.

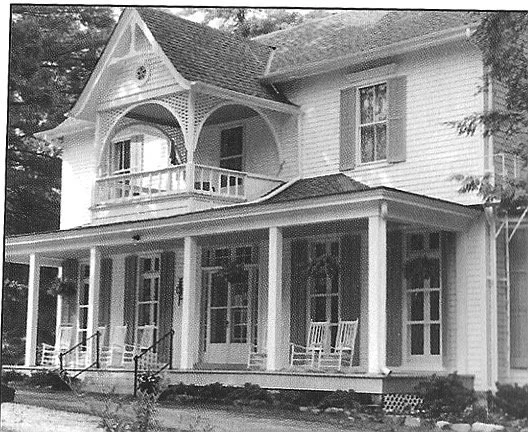

The Rock. Courtesy of the Lowndes and Burke families via Galen Reuther.

Architecturally, the Lowndes House is a two-story, wood-framed structure that features a weatherboard exterior, a traditional gabled roof, and a five-bay façade. A full-width front porch extends across the front of the house, with a small decorative balcony above.

The main entrance includes sidelights and is flanked by jib doors, which were designed to provide additional ventilation. Large bay windows bring natural light into the interior, and two brick chimneys rise from the rear of the house.

The structure sits directly on a substantial granite outcrop, which serves as its foundation and gives the property its defining identity.

Over time, the house was expanded. A one-story rear wing was added, followed in the 1960s and 1970s by additional connections to former servants’ quarters. A box office addition was later constructed to support Playhouse operations. These changes created the elongated footprint the building has today.

The result is a historic residence that has adapted to new uses while retaining its original architectural character.

Robroy FArquhar

Nearly a century after Thomas Lowndes established his mountain retreat, another figure would shape the future of The Rock.

Robert William Smith left Liverpool at age fifteen and came to the United States. By the 1930s, he had adopted the name Robroy Farquhar and formed a theatrical troupe known as The Vagabonds. The company performed in Baltimore, Hollywood, and New York, and while wintering in Miami in 1939, Farquhar first heard about Flat Rock.

He traveled to Henderson County in 1940 to explore possible theatre locations. After briefly considering Hendersonville High School, he selected the Old Mill at Highland Lake as the troupe’s first North Carolina venue. World War II interrupted those early seasons. Farquhar was drafted, and the company dispersed.

He returned in 1946 and reestablished the troupe at Lake Summit. Resources were limited, and company members took on multiple roles to keep productions running. Despite renewed success, the group still lacked a permanent home.

Ruth Conrad’s Rockworth, Now known as the Lowndes House

By 1951, Robroy and his business partner, Mendel Reddish, were living in Flat Rock on property then known as Rockworth, that included the house built by Richard I’on Lowndes.

Robroy and Mendel envisioned the property as the perfect new home for their theatre. They asked the owner, Mrs. Ruth Conrad, about leasing it for the theatre’s future. She was not immediately sold on the idea, but the vagabonds were gently persistent in their inquiry.

Then, on a spring Sunday morning, the three of them sat atop the granite outcrop with coffee in hand. “We were drinking coffee and talking,” Mendel later recalled. “Naturally the playhouse was the topic of conversation.” Finally, Mrs. Conrad said, “All right. I agree.”

With that simple declaration, Flat Rock history pivoted.

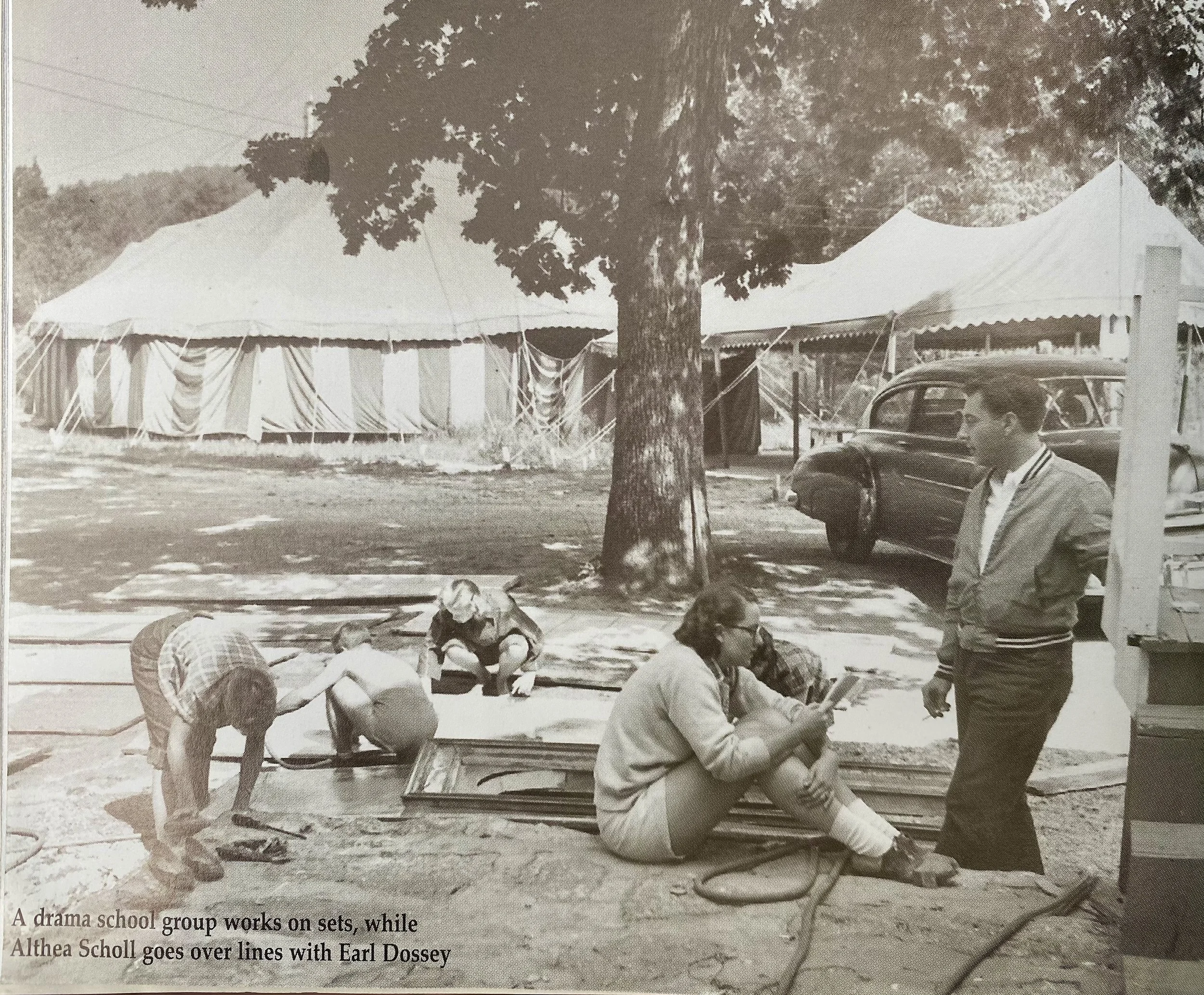

Inside the Original PLayhouse Tent

In 1952, the Vagabonds relocated to the Rock and began presenting productions under a circus tent pitched beside the Lowndes House. That same year, the company formally incorporated as the Vagabond School of the Drama, Inc., laying the groundwork for a more permanent future.

The early seasons required resourcefulness. As fundraising efforts began to replace the tent, supporters’ names were written on paper “bricks” and clipped to a clothesline during intermission. From the stage, Robroy explained the campaign to audiences - occasionally with his cat, Snodgrass, resting on his shoulder.

The effort proved successful. In 1956, trustees secured the property with a $2,500 down payment and moved forward with construction of a permanent covered theatre.

Five years later, in 1961, the North Carolina General Assembly officially designated Flat Rock Playhouse as the State Theatre of North Carolina.

What had begun as a traveling troupe performing under canvas had become a lasting institution - with the Lowndes House at the center of its growth.

A common question surrounding many of Flat Rock’s historic homes is simple: Is it haunted?

YOung Keets farquhar with actor Lew Gallo in “Apple of His Eye”

Keets Farquhar Taylor, daughter of Robroy and Leona Farquhar, offers an unequivocal answer when it comes to the Lowndes House. When asked if she enjoyed living in the Lowndes House, her response is immediate … and firm. “Absolutely not. It was haunted.”

During the Playhouse’s off-season, when the Lowndes House sat closed and quiet, a light would occasionally flick on inside a room no one had entered for weeks. Each time, Leona Farquhar would make the walk up the hill to investigate, the family dog trailing behind with visible reluctance. She would unlock the door, step inside, and scold whatever unseen presence might be responsible for wasting electricity before switching off the light and locking up again.

“She was a force,” Keets recalls with a laugh.

By the early 1990s, the Lowndes House required significant stabilization. In 1993, Flat Rock Playhouse and Historic Flat Rock, Inc. entered into a preservation easement to ensure its protection.

Historic Flat Rock provided $80,000 for restoration under an approved master plan. In return, permanent safeguards were placed on the building’s historic features - including doors, windows, mantels, floors, and staircases - as well as any major structural or exterior changes. The easement runs with the land, protecting the house regardless of future ownership.

The partnership between the Playhouse and Historic Flat Rock marked a clear commitment to preserving not just a building, but a defining part of Flat Rock’s heritage.

In the early years, Vagabonds often gathered on the back porch of the Lowndes House, sharing stories and laughter after the evening’s performance. Dennis Maulden recalls Robroy stepping out to join them - not as the director but simply another member of the troupe.

In those late-night moments, the threads of the house’s story quietly converged.

The Lowndes family shaping Flat Rock’s beginnings. Ruth Conrad’s simple “All right,”

The Vagabonds’ evolution from a circus tent to the State Theatre of North Carolina. And generations of artists who called the house home. The Lowndes House has witnessed it all. Rising from its granite foundation, it remains intricately woven into the life of the village.

And for those who feel a sense of familiarity when they see it, perhaps it is because the house has been part of Flat Rock’s story for so long that it now feels like part of our own.

References for this story:

Galen Reuther; Flat Rock’s Holiday House; https://www.flatrocktogether.com/good-news/the-lowndes-house-ca-1884

Missy Craver Izard; Diamond in the Desert and The Lowndes House, https://www.charlestonmercury.com/single-post/diamond-in-the-desert-and-the-lowndes-house

Louise Howe Bailey; 50 Years with the Vagabonds

Dennis Maulden; The Spirit of the Rock