Flight, Faith, and the Courage to Soar

/Bill Walker in the Cockpit of his Beechcraft Bonaza

The Gulfstream G4 jet banked low over the city of Kaunas, Lithuania, its sleek white body flashing in the summer light. From his window seat, Bill looked down at the airfield below, where a sea of nearly 500,000 people pressed against barricades and waved flags in celebration.

It was July 1992, and the world beneath him had only recently been reborn. Lithuania was free again, shaking off the weight of Soviet rule, and Bill Walker - successful businessman, accomplished pilot, and man who saw possibilities where others only saw obstacles - was about to touch down at the center of Lithuania’s national pride.

Bill had made the flight happen. He arranged the plane, the crew, the logistics, even the commemorative stamps for the mailbags in the cargo hold. What had begun with an unexpected phone call from a stranger, had grown into a mission to complete a legendary but tragically unfinished journey. A journey first attempted nearly sixty years earlier by two Lithuanian aviators who had vanished before reaching home.

Now, their dream was being fulfilled, and somehow, improbably, a boy who once flew small rag-wing planes off the hard-packed beaches of Georgia was leading the way.

As the jet descended through scattered clouds, Bill felt a familiar mix of excitement and awe. Those were the very sensations that had carried him from youthful tinkering with airplane engines to building auto dealerships, from nearly losing it all, to rebuilding again, and finally to flying with presidents and serving as a trusted advisor to several of the world’s newest independent republics.

In truth, Bill Walker’s story had begun long before this day on the beaches and waterways of the South Georgia coast and in the quiet mountain summers of Flat Rock, North Carolina. Yet this moment, high above a cheering crowd in a country halfway around the world, would mark a turning point - the bridge between a lifetime of adventure and an unfolding legacy few could have imagined.

-

Flat Rock resident Bill Walker grew up in St. Simons Island, Georgia, where the tides dictated the rhythm of life and the sky always seemed wide enough to invite a dream. Born in 1938 to Lucile and Quealy Walker, Bill was the middle of three children in a family that mixed Southern practicality with a streak of invention.

His father, a Tulane-trained architect turned entrepreneur, had followed his instincts into the paint business just before World War II. With Lucile’s encouragement, he built a small manufacturing company that supplied paint for the WWII Liberty ships being built in nearby Brunswick. It was a good business in uncertain times, and it anchored the family on the coast through the war years.

Bill (2nd on Right) on the Beach as a child

Though far from the front lines, the war still reached St. Simons. Nights were cloaked in darkness behind blackout curtains, and the low rumble of distant explosions sometimes shook the house. By morning, Bill and his friends might find bits of wreckage washed ashore. Yet even in those uneasy times, he managed to enjoy the innocence of childhood — fishing off the docks, exploring the inlets by boat, and spending long, barefoot days on the beach with his sisters and friends.

As he grew older and peace returned, the island gave him room to roam, to take things apart and put them back together again, to discover how the world worked by turning a wrench or tightening a bolt. “I would have worked as a mechanic if I could have made a living at it,” Bill recalls with a smile. Most of all, it was a time and place where a boy could chase a motor’s hum across land, sea, or sky.

When Bill’s father bought a plane — a kit-built Stinson L-5 Sentinel from leftover military stock — Bill’s fascination took flight. He was barely a teenager when he began pestering his father for lessons. By fourteen, he was in the air. By sixteen, he held a pilot’s license. He learned to take off and land on the hard-packed beaches of St. Simons, timing his runs with the tides, trusting instinct and touch more than instruments. Airplanes, boats, and engines were his native language. And he spoke it fluently.

The freedom of those early years would shape everything that followed. From the way Bill built his businesses to the way he approached life with curiosity, courage, and a ready hand on the throttle.

And even then, before he had words for it, there was a sense of something larger at work. Years later, when a deep faith became the compass for his decisions, he would look back and see its beginnings in those long, bright days over the island when flight still felt like grace bestowed.

Flat Rock Summers

Bill’s connection to Flat Rock reached back a generation. His mother, Lucile, had grown up in New Orleans, where the summer heat could be brutal. Her health was delicate, and from childhood she spent every summer in the cool mountain air of Flat Rock. Lucile’s father, an enterprising New Orleanian with a gift for both vision and risk, had been among the early Flat Rock summer residents.

In 1918, during one of his prosperous years, he built a home near Kanuga after a memorable scouting trip. “His chauffeur climbed a tree,” Bill said, “and told him it was a beautiful view of Hendersonville, so he bought that property and built a place on it called Arrowood Hill.”

Lucile married Quealy Walker and started a family of her own. Bill and his sisters, Sally and Gracia, were all born in September and in North Carolina. Each birth had taken place after Lucile’s final trimester in Flat Rock, and all three children were delivered at Mission Hospital in Asheville.

By the early 1940s, fortunes had turned and the family was forced to sell Arrowood Hill. Bill’s grandmother, unwilling to give up her summers in Flat Rock, bought a smaller cottage down the road and named the new family retreat, Roads End.

That was where Flat Rock truly entered Bill’s boyhood. “That’s where I learned how to drive a ’48 Buick,” he recalls. Yet for all its charm, Flat Rock wasn’t where his young heart longed to be. “I grew up on the beach,” he said. “I had beach sand between my toes. I loved everything about the beach, so I never looked forward to coming to Flat Rock. I only came under protest.”

Still, the place left its mark. Looking back, Bill would see those summers as the counterweight to his island freedom. The coast had given him motion. Flat Rock taught him balance. The two places together - one defined by open sky, the other by sheltering trees - formed the compass points of his youth.

Education and Ida

Bill and Ida on their Wedding day in 1962

Bill’s early schooling did little to change his mind about the mountains. “I went to Christ School in Asheville,” he said, “and that made me like it even worse.” For two years he boarded there, hemmed in by rules and distance from home. His heart was still on St. Simons Island, where life felt limitless. “I was free as a bird down there,” he said. “Up here, I was kind of restricted and couldn’t get around that well.”

After Christ School, he returned home to finish high school at Glynn Academy in Brunswick, GA, then went on to Georgia Tech. He spent three years there, trying to fit a mechanical mind into a world of formulas and lectures. “I struggled at Georgia Tech,” he said. “I was ADD and dyslexic. Oh, it was tough.” The structure of engineering didn’t suit him, though he loved the ideas behind it. He also admitted, with an easy grin, “I was having way too much fun.”

It was during those years that Bill met Ida, the woman who would anchor his life for the next six decades. She was three years younger and a student at the University of Georgia. Bill was a competitive water-skier, and she was a student trying to learn to ski. They became fast friends, and Ida quickly saw something in Bill that he hadn’t yet fully recognized in himself. “She realized I was really never going to be an engineer,” he said. “I was more interested in business.”

Back then, Georgia Tech offered no business courses, so Bill transferred to the University of Georgia, where his life changed direction. By then, he had learned to manage academic challenges and distractions. “I went from a 2.1 at Georgia Tech to a 4.0 at Georgia,” he said. “It wasn’t because Georgia was any easier. It was because I liked the courses, and I had learned how to study.” He also credits Ida’s positive example. “She never made a B in her life,” Bill said. Ida’s steady discipline complemented his energy and drive.

Even during college, Bill was flying planes and he took Ida on her first flight in his little Piper J-5. “She was scared to death,” he recalls with a laugh. But not scared away. Bill and Ida married in 1962, the year he graduated from Georgia.

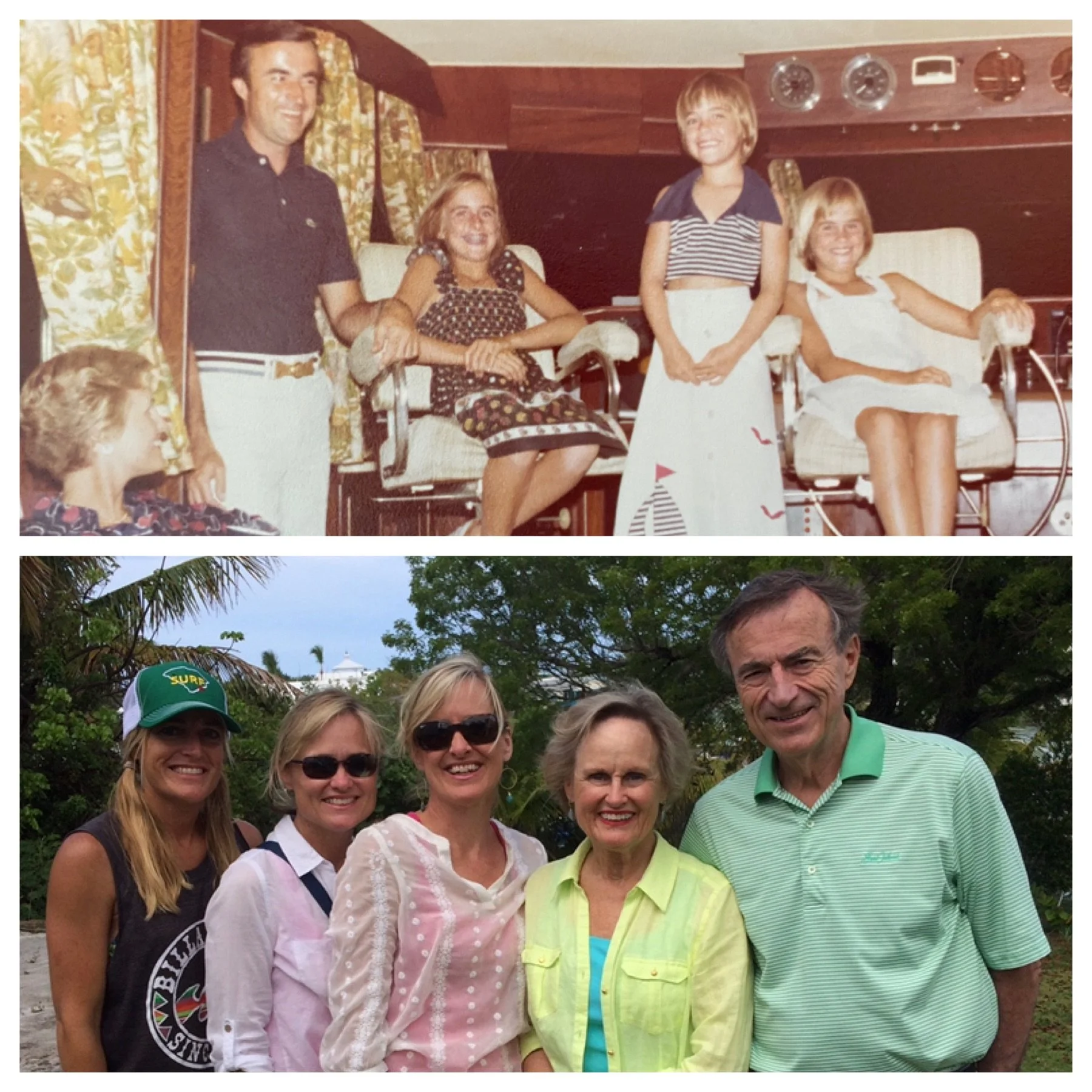

Together, Ida and Bill built a family grounded in faith, energy, and affection. Very soon they had three daughters – Robin, Gracia, and Mary Gordon - and the Walker home was a lively place filled with laughter, music, and constant motion. It was a partnership that would endure every high and low of the decades ahead.

Those early years - of finding Ida, mastering his learning challenges, and discovering his gifts - were the foundation for everything that followed. The same curiosity that once drew him to engines and propellers would soon propel him into business, risk, and reinvention.

The Automobile Years

In 1964, two years after marrying Ida, Bill went to work for his father-in-law at a Dodge dealership in Brunswick, Georgia. It was a promising start, but the young man who’d grown up tuning boat engines and flying his own planes wasn’t content to simply sell what was handed to him.

When a Pontiac-GMC Truck franchise became available in town, Bill urged his father-in-law to pursue it. When the older man declined, Bill decided to try it himself. He was 27 years old and, by his own admission, had “no money and just two and a half years of experience.”

What he did have, however, was nerve and a knack for solving problems others couldn’t. At a social gathering on Sea Island, he met Tommy Thompson, a retired general manager of Pontiac Motor Division. Thompson liked him and offered guidance. “He said, ‘Butch (Bill’s nickname), you don’t have much experience, but I’ll get you a letter of intent,’” Bill recalled. The letter promised a franchise if Bill could build a new facility and produce $100,000 in unencumbered capital.

He didn’t have the money, but he had imagination and drive. Through a friend at a local bank, Bill obtained an option on seventeen acres of a former pig farm near the Naval Air Station. At the time, the land was valued at $35,000. When he successfully pushed to have it rezoned for commercial use, the property’s value jumped tenfold overnight. That paper gain became his leverage for the capital Pontiac required. “I was able to parlay that into a hundred thousand dollars of capital,” he said.

Next came the building itself. When the original contractor died two weeks into the project, Bill and his father bought the construction company outright for $15,000 and finished the job themselves in ninety days.

By the time the doors opened, Bill had transformed a risky idea into a thriving enterprise. The Pontiac and GMC dealership quickly became one of the top performers in its region, setting sales records and earning Bill a reputation as a born entrepreneur with a talent for making good things happen.

Pilot to a President

Bill first met Jimmy Carter through a mutual friend, Carlton Hicks, an optometrist from South Georgia who was helping with Carter’s early political campaigns. Hicks knew Bill had an airplane, as well as the skill and generosity to use it. He also thought the two men would get along. “I think it was my airplane and pilot skills he wanted,” Bill said with a grin. The time spent flying Carter to campaign stops, however, soon fostered a lasting friendship. “You get to know folks pretty well sitting shoulder to shoulder in the cockpit of a plane,” he said.

When Carter became governor, he invited Bill, Ida, and their three young daughters to spend a weekend at the Governor’s Mansion in Atlanta — a highlight the girls never forgot. When Carter was elected president, the Walkers attended his swearing-in ceremony in Washington, a freezing January day that remains vivid in family memory.

Their friendship continued long after Carter left the White House. Bill occasionally flew the former president and his Secret Service detail on personal trips, one of which became a memorable adventure. Carter had asked Bill to fly the family from Sea Island to Americus, Georgia.

On board were Jimmy, Rosalynn, and Amy Carter, as well as two Secret Service agents assigned to the family. The flight to Americus proved tense. Although he had not admitted this to the former president, the plane was new to Bill, and he was not yet fully versed on the instrumentation and controls. On top of that, the weather was poor and the navigation aids around Americus were primitive. Bill surreptitiously improvised his own approach using a pocket map. “It turned out perfect,” he said, smiling. “We broke out of the clouds at about seven hundred feet, lined up right on the runway.”

That bond between pilot and passenger grew into a lasting friendship. “The Carters remained good friends,” Bill said. “We snow-skied together, fished together, and saw them a few times each year over the years.”

Rise and Reckoning

Bill and Ida in the 1960s

Success came fast. Within a few years, Bill’s Pontiac-GMC dealership was breaking sales records. It was the era of muscle cars, and his youth, enthusiasm, and drive made him a natural salesman. Pontiac Motor Division took notice, offering him new opportunities again and again. Before long, he owned eight dealerships with seventeen franchises, stretching from Valdosta, Georgia, to Brevard County, Florida, just outside Cape Kennedy.

Eventually, Bill added Toyota to his lineup, sensing a shift in the auto market. “The Pontiacs got eight and a half miles to the gallon,” he said. “The Toyotas got twenty.” He also admired the precision and reliability of the Toyotas that came off the delivery truck ready to sell, without the constant rework his Pontiacs demanded. But not everyone shared his enthusiasm. The regional manager for Pontiac accused him of doing business “with the people who gave us Pearl Harbor.”

It was a bitter lesson in corporate politics. The same ingenuity and risk-taking that had built his success now made him a target. “I began getting pickup trucks when I’d ordered Grand Prixs,” he said. Sales slowed, and with General Motors controlling his financing through GMAC, every decision became a fight. Bill was being squeezed. Litigation followed with endless depositions, delays, and expense. Bill eventually successfully settled, but the strain was heavy.

By 1975, Bill sold his dealerships and decided to step back. He was just 37 years old. “I thought I was going to be retired,” he said. The plan was to live comfortably on the installment payments from those sales, but when the automobile industry faltered soon after, many of the buyers of his dealerships sued to avoid their obligations. The years that followed tested him in ways success never had.

Bill Walker & Associates: Flight and Fortune

Bill WAlker & Associates

Not one to be deterred for long, Bill relied on his foundation of faith, mechanical intuition, and unflagging optimism to grow a new business and take flight in his next adventure. He began quietly buying and selling airplanes to help support his family. The pilot in him had re-emerged, and soon the skies would offer not just livelihood but purpose.

When Bill left the automobile industry, he vowed never again to be beholden to a manufacturer. In 1975, he turned his lifelong love of flying into a business - Bill Walker & Associates, based on St. Simons Island. The field was wide open. At the time, most airplane dealers were “mom-and-pop operations,” as Bill put it. He saw an opportunity to bring the professionalism of the car world into aviation. “I used the same techniques I did in the automobile business,” he said. “Clean airplanes, clear records, fair prices. Nobody else was really doing it well.”

Bill began by flying himself from town to town, scouring small airports for neglected planes. “I’d look for planes with half-flat tires, dirt on the wings, grass growing under them.” He’d ask who owned them, call the owners directly, and more often than not buy the plane that same day.

“All the money was in the buying,” Bill explained. “You had to find a good airplane, spend a little money making it right, and present it well. A clean airplane sells itself.” His knack for reading both people and machines turned the venture into a thriving enterprise. Within a few years, Bill Walker & Associates employed nearly twenty people, maintained up to thirty planes in inventory, and sold twenty or more a month.

The business grew alongside Bill’s expertise as an aviator. He began with small, single-engine aircraft — Cessnas, Pipers, and Beechcraft Bonanzas — then moved into larger, faster planes: Barons, pressurized Cessna 421s, turboprops like the Merlin and King Air, and eventually jets, including Citations and Hawkers.

Bill became type-rated in all of them. “I flew every day, for a lot of hours,” he said. His reputation spread quickly. By the mid-1980s, Bill Walker & Associates was featured in major aviation publications as one of the best-known used-aircraft firms in the country. “Everybody knew that if they called us, we’d buy their airplane, or we had the one they wanted.”

More Trouble Ahead

Bill and Ida with their Daughters preparing to Fly to the Bahamas for a mission trip in 1977

But success carried risk. In the mid-1980s, a general liability insurance crisis led to soaring premiums and the aviation industry was flooded with lawsuits against aircraft manufacturers and sellers. “The lawyers put the aviation business out of business,” Bill said flatly.

For independent dealers like Bill, the effect was devastating. He became entangled in dozens of lawsuits stemming from the “liability tail,” – resulting in Bill Walker & Associates being sued over planes it had sold years ago. In one case, he was defendant number 45 and sued simply because his company had once owned a plane, which was sold twice more by other people, and later crashed - with an engine not provided by Bill Walker & Associates.

By 1992, after nearly two decades at the top of his field, Bill realized he was spending more time defending himself than flying. The joy had drained away. “My people were still working,” he said, “but I was doing nothing in the world but defending lawsuits.”

The effect of the industry-wide lawsuits was devastating to the general aviation sector. Skyrocketing liability costs depressed the value of used planes, and Bill’s inventory value plummeted to just half of what he had paid for the planes. There was now a $10 million hole in his financial statements. Once again, Bill’s resourcefulness and resilience would be put to the test by the unpredictable winds of economic change.

The Phone Call

As Bill grappled with how to move forward in the face of these formidable challenges, the phone rang. It was a stranger with an even stranger request. On the other end of the line was a young man with an extraordinary proposition - one that would ultimately carry Bill halfway around the world, to the newly independent republics of the former Soviet Union.

Bill Walker could not have known it then, but that call would open the next great chapter of his life - the adventure that awaited in Lithuania.

-

Next Week: Part 2 of Flight, Faith, and the Courage to Soar. Bill arrives in Lithuania, and his next adventure unfolds.