St. John's Historic Cemetery

/I walked along the gravel path meandering among the tombstones of the St. John in the Wilderness cemetery. I was looking for a person I never met but felt like I knew well. Following a trail that runs parallel and above Rutledge Road, I eventually came to her gravesite.

The simplicity of her granite tombstone caught me by surprise. The plain gray marker belies the contributions and significance of the woman buried there. As I read her familiar name and the dates that circumscribe the arc of her life, I reflected on all the times I’ve quoted her in my articles about the history of Flat Rock. “Thank you, Louise,” I whispered.

Louise Howe Bailey

July 6, 1915

December 27, 2009

--

My visit to the grave of noted Flat Rock historian and author, Louise Howe Bailey, was prompted by my interest in the history of the cemetery that sweeps around the venerable church like a solemn verdant cloak. I was there to research the significance of the history captured on the chiseled granite monuments and inscribed marble slabs that are scattered throughout the grounds and even inside the sanctuary.

St. John in the Wilderness

In her 1995 book cataloging the history of St John in the Wilderness, Louise had written about the cemetery and the people buried there in a chapter titled, “In Memoriam.” She wrote:

In the invigorating mountain air, the summer residents found their health markedly improved. In the Church of Saint John in the Wilderness they found spiritual enrichment, and although they maintained memberships in the low country churches they attended during the greater part of the year, many chose St. John's secluded cemetery for their final resting place. Someone was heard to say, “Flat Rock is the home of my soul.” Today, a walk through the church and among the graves on the wooded hill is a journey through more than a century and a half of history. (1)

The history reflected by the names of those interred at St. John is indeed impressive and the church has created a map of the cemetery that directs visitors to some of the more significant gravesites. St. John also offers monthly tours that explain the history of the church and share stories of the people who founded, supported, and maintained the church over the course of its 188-year history. As Louise wrote in her book.

A visitor to the Church of Saint John in the Wilderness (said), “Walking through the distinguished church and the 21 acres on which it stands gives the visitor an intimate sense of the history and traditions of the antebellum South.” It is no wonder, for among shaded paths and wrought iron fences weathered stones marked the graves of men (and women) who helped shape the course of history. (1)

Churchyard at St. John in the Wilderness

Founding of St. John in the Wilderness

The website for St. John in the Wilderness speaks to the founding and early history of the church.

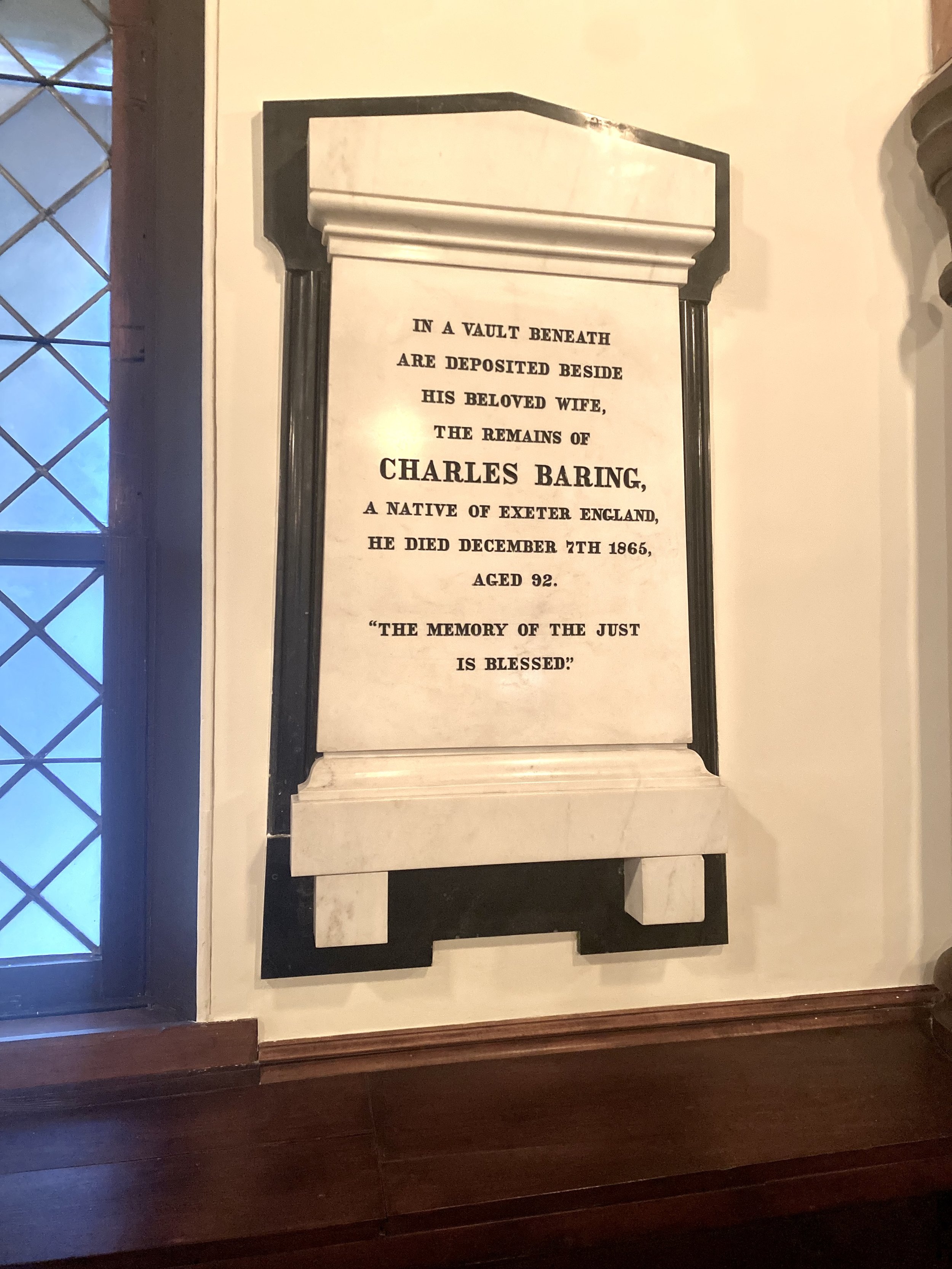

The search for a milder climate for his Welsh-born wife Susan, brought Charles Baring, a member of the Baring banking family of England, to Flat Rock to find a summer place to escape the oppressive heat, humidity, and malaria of the South Carolina lowcountry where they lived. In 1827 the Barings built a home here and named it Mountain Lodge, designed on the order of an English country estate. The house they built stands today about a quarter of a mile from the church.

On the property of their newly constructed home, the Barings built a private chapel, a practice then prevalent among the English gentry. The small wooden structure burned in a woods fire, and in 1833, work began on a second church built of handmade brick.

In August of 1836, the Barings deeded their chapel to the Diocese of North Carolina and twenty members of the Flat Rock “summer colony” formed themselves into an Episcopal parish. In the 1890s when the Missionary District of Asheville (later Diocese of Western North Carolina) was formed, St. John in the Wilderness transferred its affiliation. It is the oldest parish in the diocese. (9)

Memminger Family Plot

In an article posted on the Historic Flat Rock, Inc. website, Missy Craver Izard references the significance of the St. John cemetery:

The churchyard at St. John’s is of historic significance with graves of first families of our country, descendants of signers of the Declaration of Independence, 19th century politicians, military leaders and heroes and others of note. (8)

Local historian, Jennie Jones Giles, adds that the church was doubled in size in 1852 and a handful of graves were covered by the new footprint of the building. Until 1961, the church was only open during the spring and summer months to accommodate the families who retreated to the mountains to escape oppressive lowcountry summers. (6)

The Cemetery

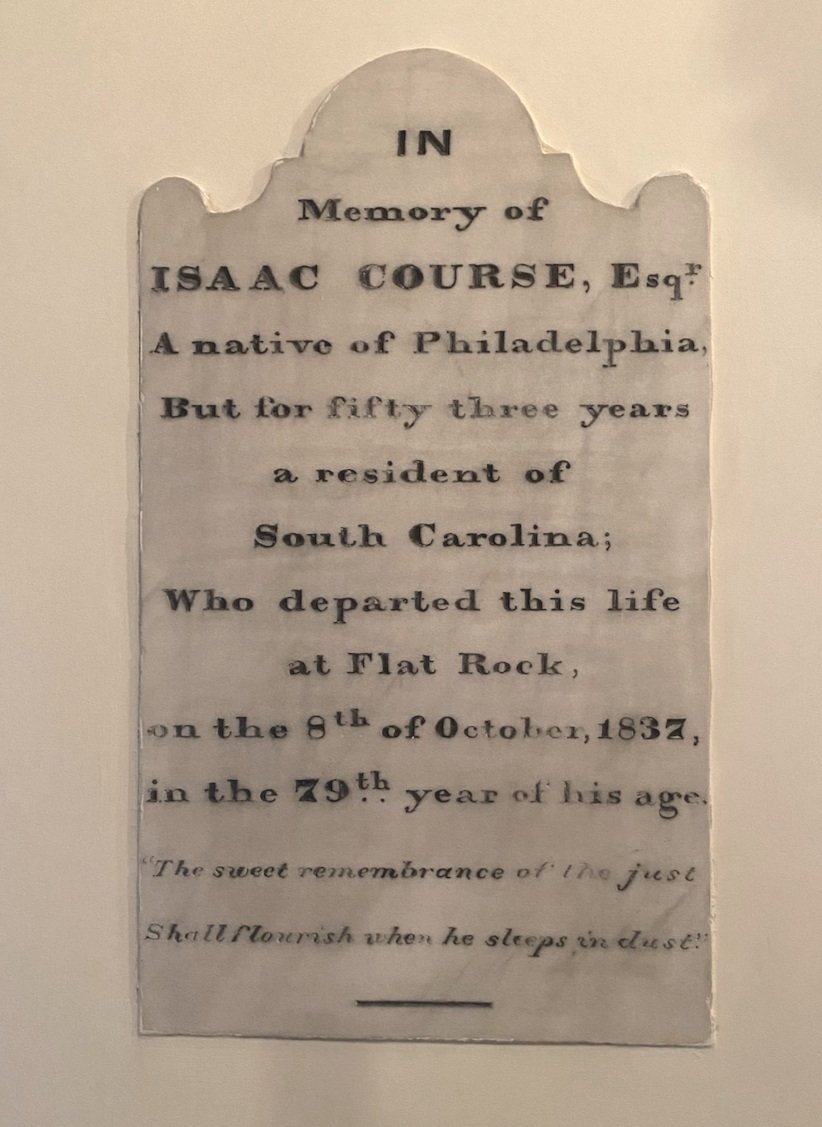

Any complete tour of the cemetery should, in truth, start inside the sanctuary where marble plaques pay homage to the founders buried beneath the sanctuary as well as the graves absorbed by the expansion of 1852. From Louise Bailey:

St. John Sanctuary with marble tablet in aisle marking the grave of Henrietta Buford.

Through the Tower entrance and a short distance down the aisle, a marble slab marks the grave of Henrietta Buford, who died in 1833. Who she was and what brought her to Flat Rock must remain a mystery, for no mention of her appears in church records. But we know that construction of the original building with 10 pews on each side of the center aisle had only begun at the time of her death and apparently no thought was given to a possible enlargement of the church in later years. When the enlargement did come about in 1852, the grave was taken into it. (1)

The Barings are also buried under the sanctuary, but by design rather than from a lack of foresight concerning expansion of the church. From the Historic Flat Rock, Inc. website:

Tablet above Susan Baring’s grave

The Barings are interred in crypts beneath the present building with marble tablets on the south wall of the church. Parishioner David Dethero told this remarkable story about the Barings’s burial place. “Many years ago, the church floors were restored. The carpet, pews, and old flooring were taken out. We were able to see where the Barings were interred. Susan Baring was buried on the South Side of the church where her pew is and her husband, Charles Baring, was buried at her feet.” (8)

Any graveyard will chronicle its share of tragedy, and St. John’s cemetery is no exception. One such sad story is memorialized with a marble tablet on the sanctuary walls to honor another grave covered by the expansion of the church building:

The same was true of the grave of little Anna Keith Memminger, child of Christopher Gustavus and Mary Wilkinson Memminger. She was drowned in the lake in front of the Memminger's Rock Hill home. (1)

The cemetery, like the enclave of Flat Rock, grew through the years and eventually required some planning to better accommodate the growing number of St. John parishioners – both living and deceased.

By 1839, gravestones had begun to appear in such numbers across the wooded hill that the Vestry agreed all future graves on the north side of the church should be so placed as to leave sufficient roadway for carriages to continue all the way around the building. Furthermore, it must be remembered that Flat Rock had been a summer resort before modern funeral practices and adequate transportation over great distances became available. It was not always possible to return the deceased to a lowcountry cemetery for burial. Therefore, in 1852, the Vestry was assigned the duty of designating a burial site for persons who had made no provisions of their own. (1)

--

Cemetery Notables

St. John’s pamphlet, “Self Guided Tour of the Cemetery”, is available to visitors who wish to stroll through the churchyard and learn more about the history of the people who called St. John their church home. The pamphlet lists some of the prominent names represented in the historic churchyard.

Baring continued to purchase land, owning 4,000 acres which he sold to other South Carolinians seeking respite from the heat and malaria - hence the names Middleton, Drayton, Rutledge, Lowndes, Hastie, Haywood, Trenholm, and Laurens - all prominent in South Carolina history. (2)

The first stop on the self-guided tour takes visitors to the gravesite probably most wrapped in legend and lore at states, “James Brown, trumpeter with the Royal Scots greys, fought Napoleon at the battle of Waterloo and was later a member of the bearings household staff.” (2)

Although there are many skeptics today, Louise faithfully reported the legend of Brown’s grave in her book:

Original gravesite of James Brown

Immediately outside the carriage entrance is the grave of James Brown, once a trumpeter with the Royal Scot’s Greys at the battle of Waterloo. With his wife, Agnes, he came to Flat Rock as a member of the Baring’s household. His name, and that of Agnes, are listed among the names of those who “form themselves into the first congregation of Saint John in the Wilderness.”

Across the years it has been rumored that on stormy nights when thunder rolls, the sound of a trumpet can be heard echoing from James Brown's grave. Be that as it may, it is known for a fact, during prohibition, moonshiners hid their wares underneath the heavy slab covering James Brown's tomb, and within a reasonable time they returned to pick up the money left in exchange. An iron rail placed around the tomb to discourage this practice apparently proved successful. (1)

The self-guided tour then takes visitors to several other names well known to current and past residents of Flat Rock. Some excerpts from the tour pamphlet include:

Andrew Johnstone was a rice planner from Georgetown SC a summer resident of Flat Rock and for many years of vestrymen of the church. During the civil war he was shot and killed in his Flat Rock home Beaumont by a band of Renegades. Who why and what prompted the act was never known.

Christopher Gustavus Memminger, first Secretary of the Treasury of the Confederate States. After a hopeless task, he resigned and returned to Charleston and introduced a public school system known to be second to none in the United States. In 1839 Memminger had built “Rock Hill”, the home that later was to be purchased by Carl Sandburg and is now known as Connemara.

(T)he grave site of Charles de Choiseul, a Confederate officer, and his mother the Countess of Choiseul. Here also is the grave of Hester Wilde an English governess to the family and charter member of Saint John in the wilderness.

The historic Flat Rock home, Saluda Cottages, was built in 1836 by the Countess’s husband, Count Joseph Marie Gabriel St. Xavier de Choiseul, French Consul to Charleston.

Monument honoring John Grimke Drayton

(A) large cross shaped marker denotes the Reverend John Grimke Drayton, a rector of Saint John in the Wilderness and developer of the Magnolia Gardens near Charleston. The adjoining Drayton plot contains Charles Drayton, a direct descendant of the builder of Drayton Hall on the Ashley river Charleston, South Carolina , whose will stipulated that no changes be made to the home.

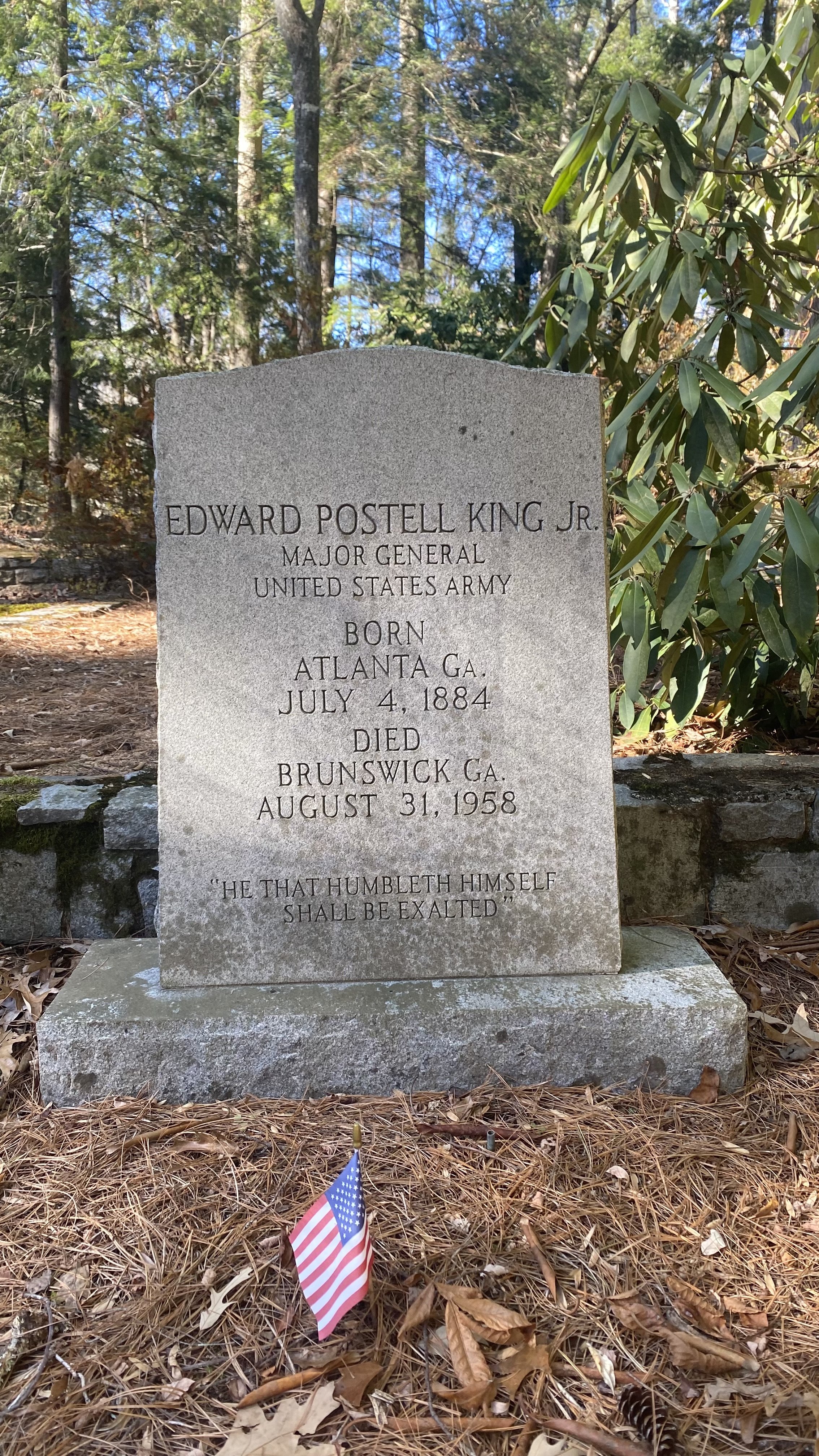

Also on the map is the grave of General Edward Postell King who was compelled to surrender American and Philippine troops to the Japanese on Bataan during World War 2 – which led the infamous death March that followed. Louise Bailey writes about General King:

General Edward Postell King, a cousin of General Alexander Campbell King, might have been accorded a hero’s rights at Arlington National Cemetery, but it had been his wish to have a quiet service at Saint John in the Wilderness. The fact that he was not a member of Saint John might have posed a problem had it not been that pew rentals were still in effect. Two of his cousins rented half a pew in his name, thus entitling him to a burial place he had wanted.

General King had represented his country in what has been called “its hour of greatest military and civil degradation” - the surrender of United States and Philippine troops on Bataan and the tragic death march that followed. Afterward he was for several years a prisoner of the Japanese, existing on rice and lying on the concrete floor of his cell while recovering from a broken hip. Respect for him as a soldier prompted the Japanese officials to hang him medallion around his neck cautioning, “Do not harm this man.” Not until he was released from prison did he learn he would not be court martialed for having surrendered against the orders of General Wainwright, who had left the island. General King's tombstone in St. John's cemetery bears the simple but appropriate inscription, “He that humbleth himself shall be exalted.” (1)

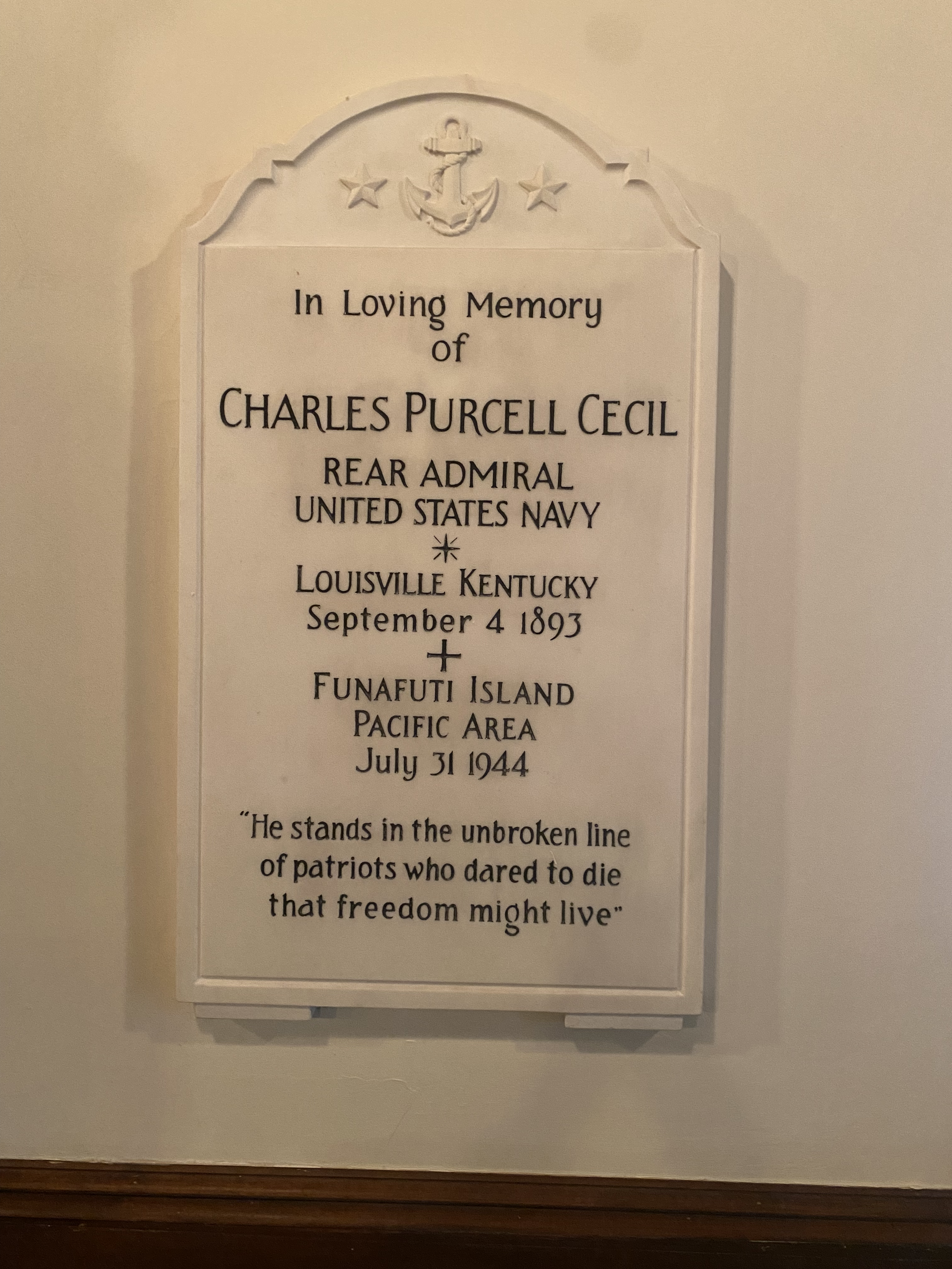

On her website Henderson Heritage.com, Jennie Jones Giles adds another story to the list of notables:

There is a memorial stone for Charles Purcell Cecil who died while serving in the Navy during World War II. He was a rear admiral and received the Navy Cross, Gold Star and Bronze Star. He was killed July 31, 1944, in the crash of a Navy transport plane while taking off from an island in the Pacific. His gravestone is at Arlington National Cemetery. He lived in Charleston, S.C., and had a summer home in Flat Rock. The USS Charles P. Cecil (DD-835) was named after him. (6)

Burial Ground for Enslaved Persons

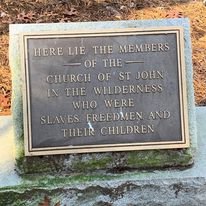

Cross honoring slaves and freedmen buried in the St. John Cemetery

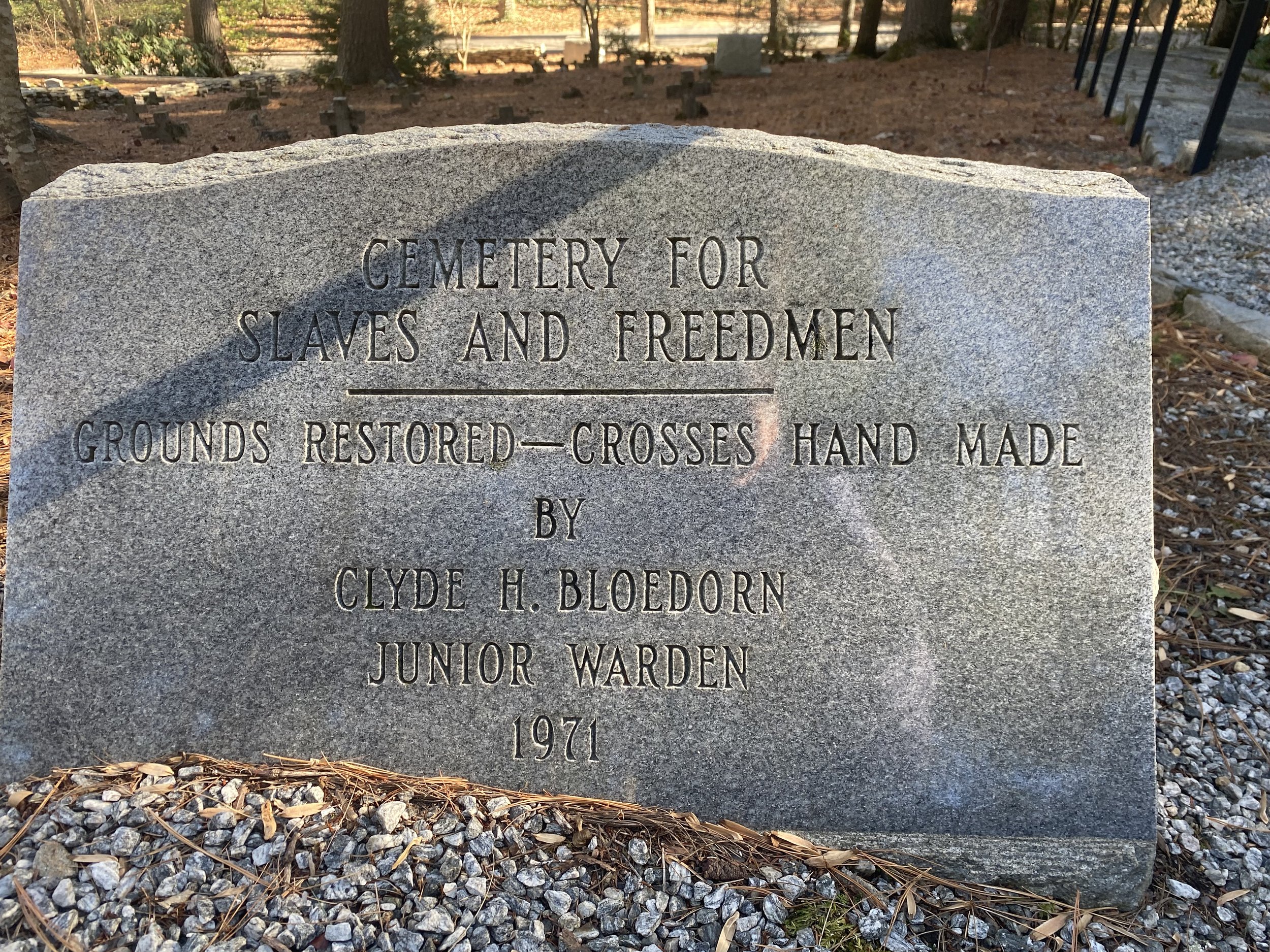

One of the most compelling stories in the cemetery is the section of the churchyard reserved for slaves, freedmen, and their children. Louise tells their story although, as was the convention at the time she wrote her book, the people buried there were referred to as “servants” when in fact a great many of them were enslaved persons:

On the wooded slope northeast of the church are graves of servants who worshipped with the summer congregation at St. John in the Wilderness. The strip of land originally set aside for those graves was deeded to the church by the heirs of Edward Trenholm. According to Vestry reports, 36 markers were found indicating burials between 1850 and 1864, although several servants were buried in the churchyard after Emancipation. Only 18 names appear in the church records, the first being that of Daniel, servant of Doctor J.G. Schoolbred, June 28th, 1850.

For many years, plain native stones marked the head and foot of each grave. In 1970, when ivy and other natural growth had obscured the stones Clyde and Dottie Blaedorn set about restoring the plot. Clyde later fashioned small white crosses of cement given by the congregation. With these crosses he replaced the simple headstones, restoring dignity and a sense of history to the burial plot and to the memory of the people buried there. (1)

Missy Craver Izard’s article on the Historic Flat Rock, Inc. website, continues the story:

About 100 graves are estimated to be in this burial ground wherein slaves and freedmen were interred from 1836 to 1881. A sizable number of their children are buried in this area, too, which is encircled by a low, stacked stoned wall created by Gerry Hunt.

In 2015, a beautiful six-foot granite cross, designed by Richard Beatty with stonework by St. John’s member Nelson Motes, was installed at the base of the African-American graveyard. At the dedication of the cross, former rector, John Morton, was quoted as saying, “I was surprised; I thought I would be just witnessing an installation. There was a lot of power, a lot of emotion.” (8)

A simple bronze plaque is attached to the front of the cross and it reads:

This memorial recognizes and honors the slaves, freed servants,

and their children who worshiped as early members of the

church of saint john in the wilderness

and were buried here, during the nineteenth century.

It is estimated that about 100 people rest at this site, their

graves originally marked with field stones. No engravings have

been found on these stones. Those buried beneath these

markers are known only to God.

Restoring the Churchyard

David Dethero

St. John’s churchyard was not always the well-planned and lovingly curated landscape that visitors will encounter today. David Dethero, who owned Hurricane Gap Nursery at the time, and joined the church in 1972, remembers the days when the grounds had a decidedly more unkempt feel about them. He was approached by parishioner Carlton Sears who established the Historic Grounds Beautification and Maintenance Endowment in 1993 on the occasion of his 50th wedding anniversary with his wife Jackie.

David recalls his initial conversation with Carlton:

Carlton said, “Now David, the landscaping around the church is disgraceful.” I said, “What do you mean, Carlton?” Because I would come to church early in the morning from the mountain, sleepy, and I'd sit on my pew, and I never noticed anything.

But when I walked around the church all we had was some dying boxwoods in the front, and some hemlocks that had been butchered. That’s about all we had around the church. So (Carlton) gave us money to do try to improve things.

In the early 2000s, as a further step in the restoration process, David and Laurie Schenck initiated a master plan to continue the restoration of St. John’s historic churchyard. Drayton Hastie of Magnolia Gardens in Charleston gifted $25,000 towards refurbishing the church grounds and graveyards and the congregation matched Mr. Hastie’s gift for a total of $50,000 for the project. This was just the beginning of an on-going effort to maintain the historic churchyard and its terraced grounds. (8)

Walking the church grounds with David recently, it is clear that his passion for plants and landscaping and the historic nature of the churchyard are an excellent match. He is characteristically modest about his work on the project for the past 30+ years. “Well, the thing is, the bones were all here. You didn't want to mess up what was here. So all we did was embellish all the trees you see here. The large trees just grew up on their own.” He adds, “So we wanted to plant subspecies trees like Japanese maples and dogwoods and red buds and some mountain things like Carolina silverbells and Paperbark maples.” The churchyard also features one section with azaleas and rhododendron hybrids that had been cultivated by Dr. Augie Kerr, one of the area’s best known horticulturists.

As I strolled through the cemetery with David, even on a cold day in December, it is easy to be impressed by both the history of the sacred grounds as well as the dedication of David and the many others who have worked tirelessly over years to maintain the grounds as a tribute to the church and the members interred in the cemetery. David summed up what I and many other visitors experience in the churchyard at St. John in the Wilderness. “The minute you step on the grounds, you just feel the presence. It's not just the history, there's a spirit here - a very strong spirit.”

Link here for information on guided tours of St. John in the Wilderness: https://www.stjohnflatrock.org/tours

References

(1) “St. John in the Wilderness 1836 – The Oldest Episcopal Church in Western North Carolina”; Louise Howe Bailey; 1995

(2) Pamphlet, “Self-Guided Tour of the Cemetery,” St. John in the Wilderness Episcopal Church

(3) “Slaves Graves”; https://docsouth.unc.edu/commland/monument/874/

(4) “Monument installed to honor early African-American church members”; Beth De Bona, Times-News Staff Writer, 12/13/1, https://www.blueridgenow.com/story/news/2015/12/13/monument-installed-to-honor-early-african-american-church-members/28335288007/

(5 ) Gaston Gazetter, ”St. John in the Wilderness Church”; https://www.gastongazette.com/story/lifestyle/faith/2019/10/07/st-john-cemetery-tour-some-history-and-ghost-story/2590291007/

(6) Henderson Heritage.com; Jennie Jones Giles; https://hendersonheritage.com/st-john-in-the-wilderness-episcopal-church-and-churchyard/

(7) Flat Rock Together.com, “He Bloomed Where He Was Planted; Missy Craver Izard; https://www.flatrocktogether.com/good-news/david-dethero

(8) Historic Flat Rock, Inc. website; https://historicflatrockinc.com/flat-rocks-st-john-in-the-wilderness-by-missy-schenck/

(9) St. John in the Wilderness website; https://www.stjohnflatrock.org/our-history

Additional Images